Resettling in the U.S.

Syrians Build New Life

Go to Photo GalleryIn 2015, Syrians were fleeing the brutal civil war as a result of a violent government crackdown after uprisings during the Arab Spring in 2011. As violence increased, people fled to Europe, Turkey, and other countries in the Middle East where refugee camps were set up. At that time, only 158 Syrian refugees had been resettled in NJ, a minimal number considering roughly 6 million Syrians have fled the country, and that there is a large Syrian community in North Jersey.

Refugee resettlements are typically handled by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as the International Rescue Committee (IRC). Once refugees arrive, the IRC furnishes an apartment for them, orients them to the community, gets their children enrolled in school, and helps obtain social security cards, food stamps, and health insurance. But little else is provided and they have to quickly learn to fend for themselves. Starting a new life in a foreign country can be overwhelming. The IRC works with the refugees to meet their goals, but the adjustment is not easy, and language is a big obstacle. When they get here, very few can converse in English well enough to find a job, often relying on Google Translate for basic communications. Plus they are usually placed in areas where there are not many other Syrians or Arabic speakers. The children tend to fall far behind in school, not only due to the language but also to the lapse in learning from the time they left their homes. And many suffer from PSTD from the trauma of war. Some have reported that their children have been bullied at school. And, of course, finding a job is daunting.

The IRC provides a comprehensive package, but the organization cannot supply intangibles like friendship, acceptance, and dignity. In NJ, there has been a growing grassroots movement by local religious groups and ad hoc volunteers to provide assistance to Syrian families trying to adapt to a new life in America. Some of that support has come from area churches and mosques, but it also came from two North Jersey Jewish synagogues.

Kate McCaffrey of Bnai Keshet said there were some members of her congregation Bnai Keshet in Montclair who were interested in getting involved with the refugee crisis. Despite the differences in faith, many members of the congregations were refugees themselves or came from families that were refugees during World War II. Bnai Keshet has invited the Muslim families for a “traditional” Jewish Christmas dinner of Chinese takeout. And during Passover, they were invited to the synagogue for Seder. The Syrians, having fled their war-ravaged homes, gratefully accepted, and acknowledged the unusualness of a Jewish synagogue hosting Muslim refugees.

Fadel Al Radi, who came with his family from Daraa, one of the most heavily bombed cities in Syria, says snipers and bombings kept his family trapped in their home for over a year. One night, a bomb struck next door killing his neighbor. A wall between the houses fell, injuring his wife Maryam, and destroying his welding shop. They lived for three years in a refugee camp in Jordan before the IRC relocated them to Elizabeth. While they are happy to be here, they’ve struggled to adjust to American customs. Fadel is frustrated that he cannot find work or speak the language.

The Al Radis have become frequent guests at the Bnai Keshet, and Maryam Al Radi and Kate have become close, although the two do not speak the same language. “They had a pretty horrible experience in Jordan,” says McCaffrey. “Maryam said that they were treated very badly. They have been struggling to re-establish themselves.”

The U.S. is one of the few countries that require refugees to pay back their travel costs after they are resettled. The Al Radis, who have four children, received notice that they must start to make monthly payments. The Al Radis, who have no means of income, panicked. Bnai Keshet stepped in to help. McCaffrey started a GoFundMe page; the congregants quickly raised the nearly $7,000 needed to pay off the debt.

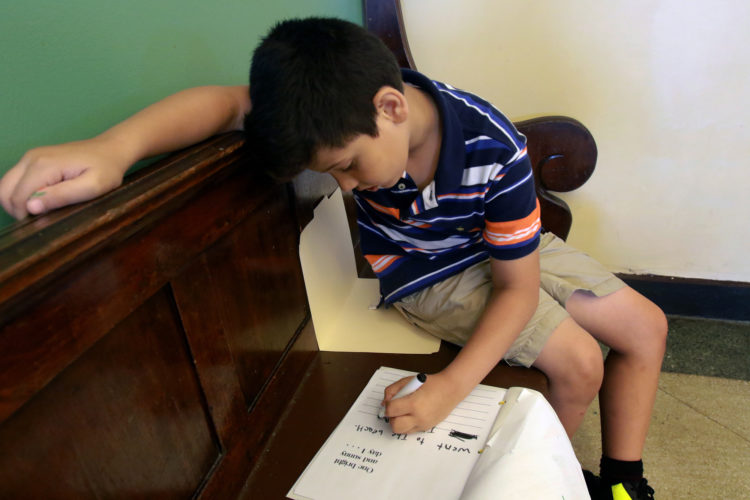

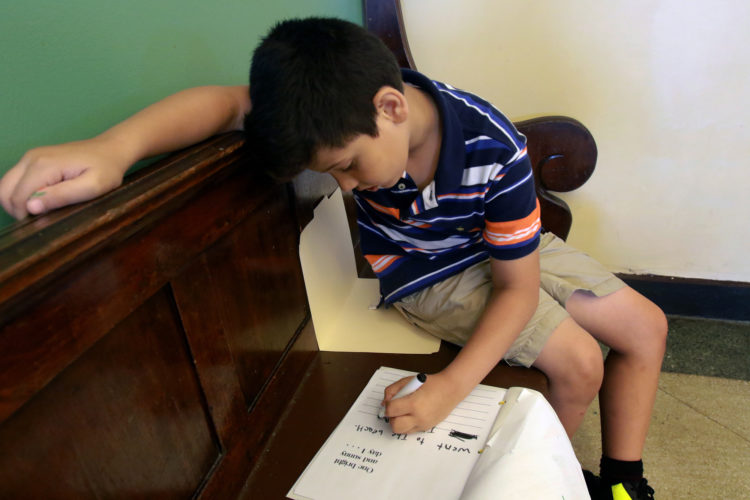

Mohammad Ali Zakkour says that his former life in Syria was very good. He had his own clothing alteration shop, and he was able to support his wife and children comfortably. Then the war changed everything. Like many Syrians, the aerial bombings and street fighting forced Zakkour and his family to leave everything behind and flee to Jordan before the IRC placed them here. Learning the language is the key to finding work, so regularly attends tutoring sessions. Again, Bnai Keshet stepped in and raised money for a sewing machine so he would have a way to generate income.

Zakkour is appreciative, and he wants to teach his children that religion, race, and gender should never get in the way. He’s very grateful he found people who feel for him and his family. “We are all brothers and sisters in humanity,” Zakkour said. “I want to teach that to my kids. I want to plant the seed.”

In July 2019, NJ Governor Phil Murphy announced plans to take back control of the state’s refugee resettlement program, after former Gov. Chris Christie attempted to keep Syrian refugees out of New Jersey over security concerns. Murphy also signed an executive order to create an Office of New Americans, which will be the first statewide office to focus on integrating immigrants and refugees into New Jersey.

By 2019, the Al Radis were living in Michigan, and still adjusting to life in the US. The Zakkours remained in Elizabeth and have added a baby girl to their family, and are doing well. McCaffrey co-founded the Syria Supper Club, which brings together New Jerseyans and refugees, to share a meal prepared by the Syrians.

- Read full story and see photo gallery by Thomas E. Franklin in NJ Spotlight.

- Listen to radio interview with Thomas E. Franklin on WNYC’s Brian Lehrer Show.

Undocumented man turned over to ICE Despite Newark’s Sanctuary City Status

Newark, NJ

August 2018

Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan think tank, estimates the number of unauthorized immigrants living in the U.S. is close to 10.5 million, down from a peak of 12.2 million in 2007.

In New Jersey, which has a large community of immigrants, the report estimates that between 2007 and 2017, the population shrank from an estimated 550,000 to about 450,000. The countries from which unauthorized immigrants are coming include El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and increasingly from Venezuela.

In 2018, undocumented Newark resident Daniel Castro was taken into custody by Newark Police for an outstanding warrant In June 2018. At the time of his arrest, Castro was in a car returning from getting bottled water for baby formula. His would-be father-in-law was driving when police pulled the vehicle over for making an illegal U-turn. After he was unable to produce identification, Newark turned him over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and he was taken to the Elizabeth Detention Center.

His life would never be the same.

At that time, Castro was a 28-year-old construction worker, with a fiancé and a newborn son. He never had an issue with the law in the 15 years he has been in the United States. But when the police ran his name in their database, they discovered an ICE arrest warrant for deportation. It turns out he missed an immigration court hearing in 2011. He says his lawyer at the time never notified him, that he knew nothing about the appearance or the ICE warrant. (There are different types of immigration detainer requests, and an ICE warrant is an Administrative Warrant issued by ICE and not the same as a judiciary warrant, which is an arrest warrant issued by a judge.)

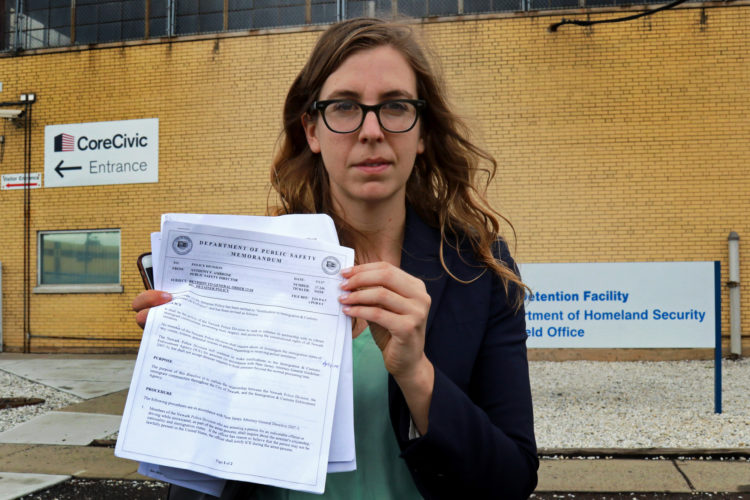

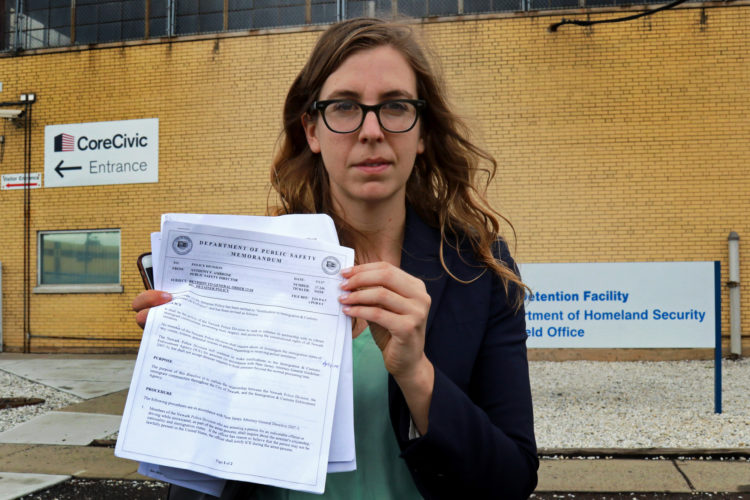

What makes Castro’s case so unusual was the fact that Newark is a self-designated Sanctuary City. Its policy pledges to protect undocumented residents with no criminal history from ICE. Immigrant rights advocates contend the police may have overstepped by taking him into custody.

“The fact that Daniel was identified and flagged and then subsequently detained by Newark police for his immigration status issues and that he was turned over to ICE without actually being charged with any crimes is a very clear violation of the sanctuary policy as well as the Newark police directive,” said Chia-Chia Wang, the advocacy director of the American Friends Service Committee Immigrant Rights Program, which helped draft the policy for the mayor’s executive order. At the time, Newark police and the Mayor’s office said they were waiting for the results of the investigation, but later admitted there was wrongdoing by the police and the officers involved were disciplined. The city now has a new training procedure for handling such cases.

Danny Castro’s story is not unlike thousands of other undocumented immigrants who now find themselves facing deportation after President Donald Trump’s executive order that expanded the definition of “criminal aliens” and increased its crackdown on those who may have entered this country illegally.

He said life in Nicaragua was rough, his family had little money, and the country was in political turmoil. There was pressure to join the Sandinistas, the left-wing Nicaraguan political organization that overthrew the government, but he said he didn’t want to fight for a cause he didn’t believe in. So he came to the US when he was 13 with nothing more than $20 in his pocket. He became skilled in construction and found steady work.

Kasandra Serrano, 21, said she and Castro met through some friends in 2015, and have been together ever since. They now have a young son, but she says without Castro’s support, she has moved in with her mother and is struggling. She says she doesn’t know what she will do if Danny gets deported.

Castro was locked up in ICE detention in Elizabeth. His attorney Lauren Major filed a motion which argued that he is eligible for immigration status in the U.S. on several different grounds. But the motion was denied.

After this story was published in August 2018, an immigration judge ruled against Castro, and he was deported back to Nicaragua. Major says she filed an appeal on Danny’s behalf back in early 2019, but they have not received a decision yet.

In 2019, asylum-seekers submitted 2 million new claims for resettlement. Despite the Trump administration’s restrictive immigration policies, the United States remains the world’s largest recipient of new individual applications (301,000), according to the UNHCR.

- Read full story, photos and video by Thomas E. Franklin in TapInto Newark