Seeking Refuge | Images of Those Displaced by War, Poverty, and Persecution

The world is currently witnessing the highest levels of displacement of people from their homes on record, as an unprecedented number of people around the world have been forced to flee their homes due to conflict and persecution.

According to the annual Global Trends Report’s latest report released by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in June 2020, nearly 79.5 million people were displaced at the end of 2019, with over a 100 million people newly displaced during the course of the past decade.

These are staggering numbers.

Experts have called the situation the worst refugee crisis since World War II, as war, poverty, and persecution continue to drive record numbers of people from their homes worldwide. This crisis has been heightened by disturbing stories and images that continue to emerge from detention centers along the southern United States (U.S.) border, in Greece, and elsewhere.

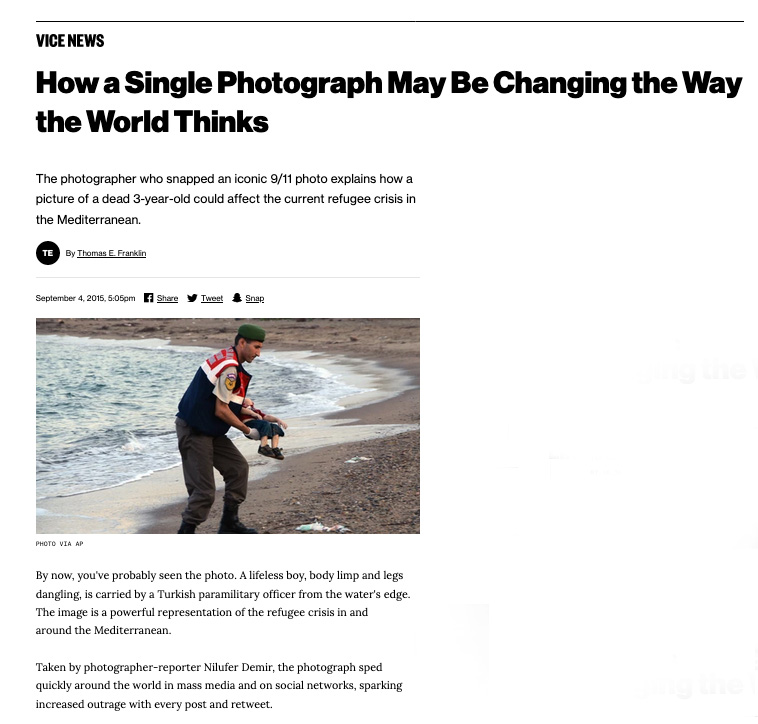

I first became consciously aware of the refugee crisis in 2015, when I saw the horrific image of a lifeless 3-year-old Syrian boy named Aylan Kurdi, body limp and legs dangling, carried by a Turkish paramilitary officer from the water’s edge in the Mediterranean Sea. He and his family were Syrian refugees trying to reach Europe amid the European refugee crisis. Taken by photographer-reporter Nilufer Demir, the photograph sped quickly around the world in mass media and on social networks, sparking increased outrage with every post and retweet.

In September 2015, VICE commissioned me to write an opinion piece about the image. It was and still remains a powerful representation of the refugee crisis in and around the Mediterranean.

Read How a Single Photograph May Be Changing the Way the World Thinks, by Thomas E. Franklin, in VICE.

See Did the picture of a dead Syrian child change anything? TV interview with Thomas E. Franklin on Turkish television, TRT World.

The photo is chilling and unforgettable, as many great photographs often are, and it inspired me to focus my attention on the issues surrounding forced migration. I began with the crisis in Syria, because the brutal civil war was raging at the time, but also because locally here in New Jersey where I live there is a large and established Syrian community. “All news is local,” a news editor once told me, thus began this exploration of various topics related to forced migration and immigration, not just here in New Jersey, but to the U.S. southern border, to Central Mexico, and to Greece, not far from where young Aylan Kurdi lost his life.

Conflict and extreme economic challenges are the leading causes of involuntary displacement, whether it be Syria’s deadly civil war or crushing poverty and failure of governments in Central America, or Venezuelans concerned over human rights violations, violence and food insecurity. The most recent findings of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) released in June 2020 shows that nearly 79.5 million people were displaced at the end of 2019 which is roughly 1% of the world’s total population, or 1 in 97 people, including 45.7 million people displaced internally within their own country. These numbers are nearly double the 2010 number of 41 million. These are the highest numbers in the organization’s almost 70-year history. And they are rising.

Perhaps even more alarming than the growing numbers is the increasing hostility toward refugees globally, particularly in developed countries like the U.S., whose governments have historically pledged to assist asylum seekers as per the 1951 Refugee Convention. Also known as the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, this United Nations treaty grants any person the right to ask for asylum in a country that has signed the agreement. It also gives them the right to remain there until authorities have processed their claim. The U.S., for example, is part of that treaty, as is Greece, and all the countries in the European Union.

Accepting refugees can be problematic for any country, as there is always competition for resources that can stir anger and mistrust among the tax-paying population. Concerns that they can become an economic drain on the countries that welcome them and the impact the influx refugees can have on labor markets are often cited as the leading causes of concern. But experts say it is difficult to fully understand the economics of massive migrations without careful, thorough research on its rippling effects over time.

As an independent freelance multimedia journalist, over the past six years, I have explored and published a stories, both personal and collective tales of people seeking safety in foreign lands. I have visited places abroad where the forcibly displaced are at the most vulnerable, such as in Lesvos, Greece, and Tijuana, Mexico, as well as here in our local communities in New Jersey, in hopes of better understanding the impact forced migration has had on these asylum seekers (or refugees). In each of these places, the vast majority of people I met said they would be willing to do whatever it takes to gain a better life for themselves and their families, no matter the risk because the place they left was far worse.

There are seven separate photo essays presented in this project; each bears witness to both historical events and the more subtle shifts in cultural attitudes that speak to the historic migration. They depict the experiences of many who are currently displaced and shed light on the highly complex circumstances surrounding global migration. It also examines the hotly debated effectiveness of increased border fortification between the southern U.S. and Mexico. It also documents the experience of the newly arrived and the first-generation immigrants as they assimilate into American culture in New Jersey.

One of the most surprising aspects of this project has been the unprecedented engagement of non-profits, ad-hoc volunteers, and global grassroots organizations. These agencies provide invaluable legal services, medical care, and other types of support to refugees and their children. These organizations also help ease the pressures on host countries by providing what they cannot – humanitarian aid, comfort, and friendship.

In each place I traveled, I heard strong arguments about whether to accept refugees or not, from both sides of the debate. As a journalist, I try to approach this emotional issue from a neutral political position. While at the same time, I believe refugees are among our most vulnerable populations. And that empathy and collective responsibility for their safety should be the shared goals of everyone, for the greater good of all people.

The refugee crisis is a complex, hot-button topic, a humanitarian crisis that shows no sign of abating.

Technical note: All images are original documentary photographs captured by multimedia journalist Thomas E. Franklin who works in both video and photography mediums – often simultaneously. A small number of the photos are frame-captures from video made in situations where still-photography was not possible. These video images were captured in the field and converted to still images in post-production.