Migrants Coming to the U.S.

Migrants Make Grueling Journey North

Go to Photo GalleryDriven by dire economic conditions and rampant violence at home, and a desire by many to reunite with relatives already in the United States, thousands of migrants from Central America make the long and dangerous journey through Mexico each year. Most seek asylum, but the wait times for their cases can take many months or years.

In 2017, President Trump implemented increased vetting for refugees, which slowed the process of admissions. Furthermore, the Trump administration reduced the number of refugees the U.S. accepts annually. As a result, many attempt to come into the U.S. illegally instead.

In 2018, Central American migrant caravans made huge headlines. Large groups were crossing the Mexican border to make the long arduous journey north to the U.S. border with the idea that there is safety in numbers. But it is also physically demanding, especially for families with young children who walk for hours at a time in the blistering hot Mexican sun.

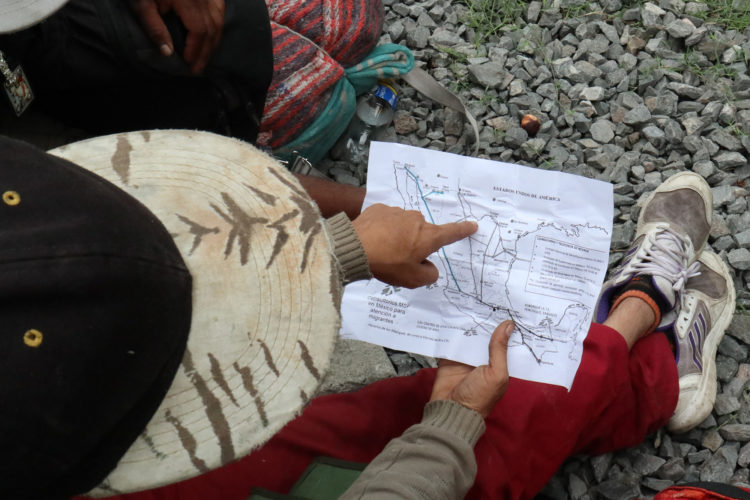

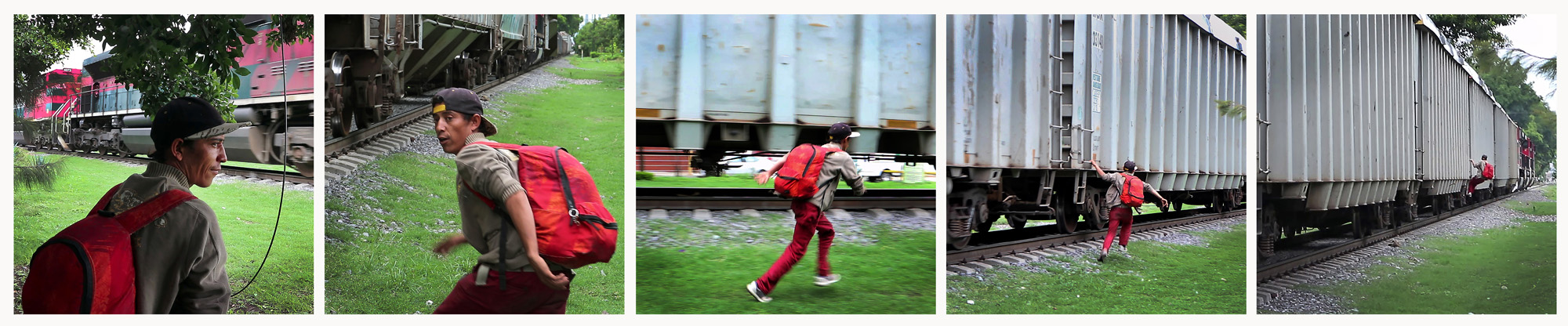

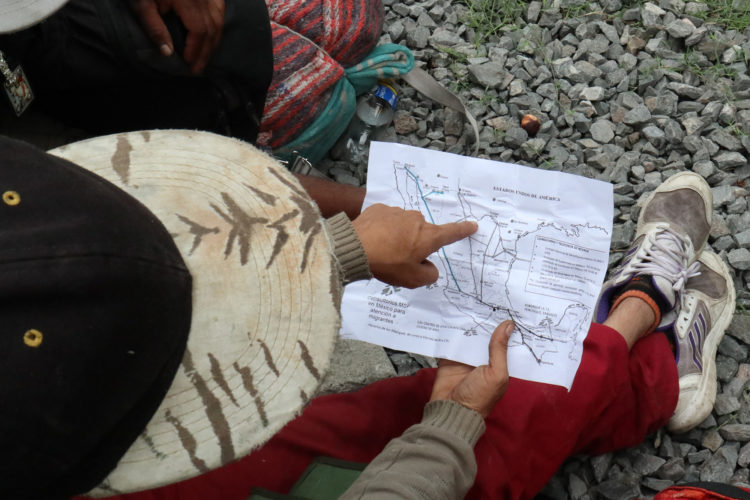

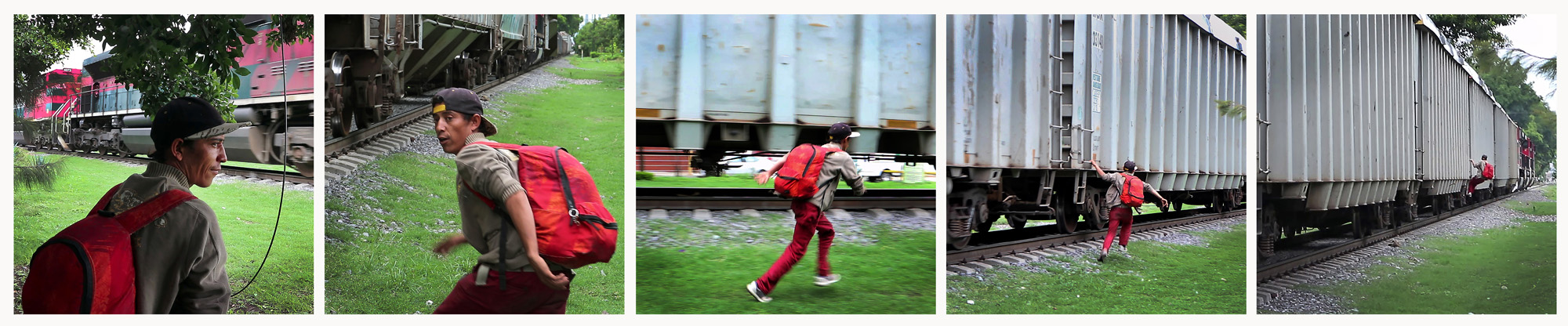

For decades, migrants have made the trip north to the U.S. border by stowing away atop freight trains, to more quickly and inexpensively traverse the length of Mexico. The ride aboard the trains, known colloquially as La Bestia, The Beast, or the Train of Death, is harrowing with the specter of amputation or death if you fall or get pushed. Over the years, many have lost limbs or their lives. Migrants say the key is to grab hold of a railing or ladder and hoist aboard without losing grip.

Migrants are also often subjected to extortion and violence at the hands of gangs and organized crime groups that control the rail lines north, and prey on the helpless. According to the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), an estimated half-million migrants ride La Bestia each year, which runs along multiple lines. This mode of travel is also illegal. Central Americans require a visa to travel through Mexico, which most cannot afford, plus there are no ticketed passenger train routes traversing all of Mexico.

MPI reports that migrants riding La Bestia are likely to be among the poorest and most desperate, and prior to the recent rise in migrant caravans, La Bestia has proven to be the only viable option to reach the north. Those hitching a ride on the freights are also less likely to have contacts in the U.S. who can connect them to trusted smugglers, or help fund the journey. Fees for smugglers, known as “coyotes” go as high as $10,000 per person, far beyond the means of most migrants. Others consider drug smuggling for cartels, or prostitution, in exchange for transport. Despite the danger and inherent risk, hitching onto a freight as a stowaway is often the only option.

Mario

Guadalajara, Mexico

July 2017

When I met him in July 2017, he was in Guadalajara, roughly in the center of Mexico. He was staying at FM4 Paso Libre, a popular and resourceful shelter for migrants and their families run by volunteers. He had recently returned home to Honduras to help his ailing father, and n was attempting to return to Florida, where he had a job and a son. After traveling for over a month, he was now resting up at FM4. He made friends with a group of Hondurans he met at the shelter; he said he was ready to leave FM4 to continue north.

Mario said he was not deterred by anti-immigrant attitudes in the U.S. despite the recent crackdown on undocumented migrants entering in the U.S. He loved living in the U.S., and he had no choice but to cross illegally if he ever wanted to see his son again, Mario said.

The Hondurans set out in the middle of the night plotting to catch La Bestia. Mario said they had no train schedules, but they heard that it might pass through GDL that morning around 3 AM. They headed towards a spot in an industrial area where the train often slowed. He carried nothing more than a knapsack with water, snacks, and some personal items.

Hours passed as they walked along the tracks, anxiously, through gang-controlled areas where wild dogs roamed menacingly. The tracks were littered with debris and broken glass. Finally, they heard La Bestia coming. The rails lit up from the oncoming headlights, the fast-moving train was upon them quickly. They stepped up at arm’s length from the passing rail cars, scanning each passing car, looking for a ladder to grab onto. The sound was deafening. But on this night, the train was moving too fast, and it passed without any of the migrants able to get aboard. Mario said afterwards it was too dangerous. They walked some more, before setting up camp on the tracks and waiting for the next freight to come through.

After that night, I kept in touch with Mario via Facebook. Mario and his crew got on La Bestia the next day, reaching the border about a week later. He then spent the next few months living in the Mexican border towns near Mexicali plotting his next move. He occasionally sent messages and photos to me via Facebook whenever he had access to a phone or computer, but then I lost track of him for many weeks. It turns out he crossed over into California illegally sometime in late 2018, and made it up to Los Angeles, before being deported back to Honduras by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), where he currently lives.